Originally posted December 24, 2010

Originally posted December 24, 2010

Sitting in the mosque board meeting, as one issue after another was raised, I’ll confess it was difficult not to drift into my own thoughts. However, one issue was raised that caught my attention that was, perhaps not surprisingly, the issue of finance and fundraising: the mosque needed funds for refurbishing the ablution (wuḍu) area. Without much progress being made, I identified a possible source, although it was not problem-free. The source I suggested had a large proportion earned from unlawful sources; however, there was an opinion within Fiqh (jurisprudence), which allowed the utilisation of such funds for public good (maslaḥa).1 This objection was fairly raised by some, but as I started to explain how there was a scholarly opinion – “Forget the scholars!! We only follow the Qur’ān and Sunnah,” shouted a fellow member, whom I found uncharacteristic since this brother seemed to be a calm person. He then explained how Muslims should follow the Qur’ān and Sunnah only and leave aside the scholars to their own mumblings. Unfortunately (or perhaps fortunately) he was older, held a more senior position than me, and most definitely had a louder voice than me and thus the saying “might makes right” had full effect. I looked down; although they took on my suggestion, I was somewhat frustrated at the rather superficial understanding of Islam this brother manifested. He was a brother of good character and a person who usually has a very pleasant demeanour, yet even he, when it came to Fiqh, could not escape this intolerant attitude.

This article aims to briefly take a look at the claim of some who say that they follow nothing but the “Qur’ān and Sunnah” or only the “Qur’ān and ṣaḥīḥ Ḥadīth.”

What is the purpose of this slogan? By merely using this term it seems a person alleges that any community member who does not affiliate with their group or understanding is not following the Qur’ān and Sunnah. When a person juxtaposes a valid legal (Fiqhī) opinion you’re following with “but you should follow the Qur’ān and Sunnah,” it implies that you aren’t. This attitude suggests truth is the monopoly of his/her group and the rest of the people are doomed.

What this also shows is that a person who takes this stance shows a lack of understanding of the process, by which the primary sources – the Qur’ān and Ḥadīth – are interpreted, and through which conclusions are reached.

Understanding How the Scholars Understand (fahm)

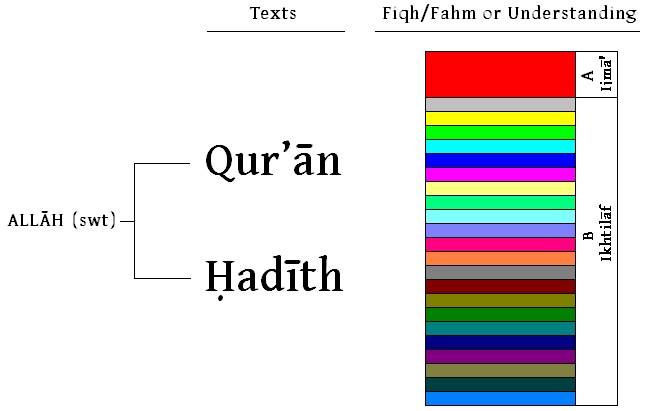

Look at the following diagram:

Figure 1

The primary sources in Islam are the Qur’ān and Ḥadīth, both which originate from Allāh. Whilst the Qur’ān is directly from Allāh using His words, the Ḥadīth is relayed to us through the words of the Prophet ﷺ though the meaning is from Allāh. These words are then recorded in the form of a text, thus both the primary sources are texts. These texts are then understood by scholars/jurists/interpreters in efforts to decipher what God intended.2 This forms what is known as ‘fiqh’.3

One Understanding

Now in some issues (A – Ijmā’), there is only one understanding, one fiqh (as indicated by the red key colour in fig. 1). This means that the whole community of jurists are certain that what they have understood is actually what God intended. This is because either:

- The primary sources are clear-cut (Qaṭ’ī) in both their authenticity (thubūth) and meaning (dalāla). For example: the belief in monotheism, in the hereafter, the fact that the five daily prayers are Farḍ (obligatory).

- The primary sources are unclear (Dhannī) in either their authenticity or meaning, however a clear (ṣarīḥ), legitimate and genuine consensus has been reached. This means that there is a consensus and not just a claim of consensus.4 Yet such issues of agreement form the exceptions rather than the norm, as a brief look at any encyclopaedia of Fiqh proves. Based on this, Ibn Hazm explains how consensus is often erroneously claimed.5 What is interesting is that Ibn Hazm himself, may Allāh reward him, seems to fall into this error when he drew up his own list of issues in which he thought a consensus had been reached.6 Ibn Taymiyya later followed up Ibn Hazm’s list of issues of alleged consensus, and showed some areas in which Ibn Hazm erroneously claimed a consensus, when there was in fact none.7

Thus in such issues everyone is “following the Qur’ān and Sunnah,” therefore repeatedly chanting “only Qur’ān and Sunnah” is made redundant.

Many Understandings

Most issues however have a wide range of scholarly understandings (fig. 1. B – Ikhtilāf, the different views indicated by the different colours), all of which do go back to the Qur’ān and Ḥadīth. These varying views may be due to several reasons, which can be summarised into the following8:

- While the sources that relate to the particular ruling are agreed upon, the understanding of that Ḥadīth differs; hence it is the fahm (understanding) that is leading to the Ikhtilāf (difference of opinion). A clear example of this during the time of the companions is the incident of the cAṣr prayers at Banī Qurayẓa.9

- The source in relation to that issue is differed over, due to reasons such as a dispute in authenticity, or whether it was abrogated or not, or whether it is related directly to the issue under discussion.10 Thus whilst some jurists use a certain Ḥadīth and base rulings on it, others do not due to the aforementioned reasons.

Less Than Certain – Still No Rebuking

Sometimes jurists are not 100% certain that what they have understood or the ruling that they have arrived at is actually what Allāh had intended. This follows the process as:

- Their understanding/views are all based on a sound interpretation (Ijtihād);

- The primary sources are not clear-cut, which means Allāh deliberately did not reveal His will clearly;11

- There is no other means of verifying the will of Allāh other than through understanding the primary sources, since revelation has ceased with the demise of the Prophet ﷺ.

No one can condemn another for holding a valid view. “There is no inkār (rebuking) in matters of ikhtilāf12” and “an Ijtihād is not made redundant by another Ijtihād13”. This means that such differences will always exist and no amount of insistence on “ṣaḥīḥ Ḥadīth” will help unify them.

Is There A Way To Certainty In Such Issues?

No. The only situation in which one can be fully certain (Yaqīnan) that he is on the correct opinion in issues to which the primary sources are less than clear-cut, is if they receive further clarification from God. This is known as revelation (waḥi). Now this happened with the Prophet ﷺ when he made an Ijtihād and decided to take ransom from the captives of the battle of Badr. The companion Abu Bakr (ra) agreed with the Prophet ﷺ but `Umar (ra) disagreed. Allāh agreed with `Umar (ra) and made this known to the Prophet ﷺ using stern words (Qur’ān, 8:67-68) which caused the Prophet ﷺ and Abu Bakr (ra) to weep. As the Prophet ﷺ is no longer with us, and there is no prophet coming after him, this medium of clarification from God has ended, and thus no one can claim such an authority. And even if they did, they would have gone against clear-cut (Qaṭ’ī) texts, which negate such a possibility (i.e. wahi) after the Prophet ﷺ and thus anyone claiming this would be committing blasphemy and render their Imān (faith) void.

Points to Consider

There are several points,14 which are worth keeping in mind so that the simple notion of “only Qur’ān and Sunnah” can be avoided.

1. An Oversimplified Perception

If all that has been mentioned is understood, then it is simple to see how futile it is to continuously hurl the slogan of “only the Qur’ān and ṣaḥīḥ Ḥadīth15” especially in matter of difference of opinion (disregarding the reasons as to why the differences arose in the first place16). Indeed as Ibn Taymiyya stated,17 such differences arise rarely because the scholars based their opinion on whim or arbitrarily formed rulings. If that was the case, then chanting “ṣaḥīḥ Ḥadīth” is understandable, as one would think, “if only they knew of the Ḥadīth, then all differences will cease.” However this is not the case, thus it is useless to suggest that by following the Qur’ān and ‘ṣaḥīḥ’ Ḥadīth, all differences will cease.

Consequently, every time someone acts upon an opinion about which the Qur’ān and Ḥadīth are not clear, they are following an understanding of someone. This person can be a scholar or a non-scholar. Thus Ḥanafis, Mālikis, Ḥanbalis and Shāfi’īs are simply being honest when they admit that they are following one understanding of the primary sources out of many. However the person who refuses to adhere to the legal schools mentioned, nor admits to following any other scholar/jurist, but instead claims to follow the Qur’ān and Sunnah directly, and independently, the question remains: whose understanding are they following?18

2. Pretentious Certainty

Moreover what this also shows is that if someone, a scholar or non-scholar, gives the impression that their view regarding a dhannī (unclear) matter, is somehow objectively the only correct view, that somehow they have by-passed the ‘fahm’ as indicated in fig. 1 above, and have approached the Qur’ān and Ḥadīth directly as they may say, then one should be cautious of this person’s methodology, as this is impossible. His opinion is only one of many (as indicated by the different colours in fig. 1). One cannot deny history, or the natural human process of interpretation. Every text thus approached and every ruling issued, was achieved by the human agent through interpretation. If one is not a prophet, then one cannot claim to have just ‘known.’ This means that there must be a methodology upon which such an understanding was based on. It is vital that we know what this methodology is to see the logic and evidence of the said opinion. If this is the case, and this person is denying this very human aspect then either:

- They themselves are unaware of their methodology and somehow think that they are actually approaching the texts ‘directly,’ similar to how Prophets receive information disconnected to history and context.

- They are either knowingly or unknowingly (good opinion obliges us to hold the former) hiding their methodology, to inject their opinion with an aura of false objectivity, and through this they wish to acquire more followers. In other words, to put it in bluntly, it is merely a marketing ploy.19

An Example

This attitude also seems to manifest itself towards how people approach the text Fiqh al-Sunnah. It is as if many people have misunderstood the purpose of the text and think this is literally what the title suggests, “The understanding of the Sunnah” without the human agent or fahm. Yet this is belied by the fact that the author, Sayyid Sabiq, states various understandings when he covers the many different issues. Thus to take this book as representing the ‘real Sunnah,’ and to take for example the Ḥanafī text Mukhtaṣar al-Qudūrī or the Maliki text Mukhtaṣar al-Khalīl as being ‘biased’ shows that one clearly fails to understand the dynamics of text-understanding, since if this applies to all human beings, it surely applied to the author of Fiqh al-Sunnah.20 The blame in such a case however, rests on the reader and not on the author. One must be careful of a fetish for certainty in an area that offers none. Such indulgences are as bad as the desire for speculation in an area which is clear-cut

1. The Secondary and Tertiary sources

Another obvious fact that seems to be ignored when one insists everything must be mentioned from the primary sources explicitly is the negation of several other sources, secondary and tertiary. The fact is that everything is not explicitly mentioned in the primary texts (Qur’an and Sunnah). A quick look at the Islamic Juristic legacy shows that not only were there primary sources, but based on this, there were also secondary sources of authority – Consensus (Ijmā’) and Analogy (Qiyās) as well several tertiary sources. Moreover, there were different maxims developed after scholars’ surveyed different rulings in order to facilitate the jurist to encompass them with ease. This attitude also overlooks the highly developed maqāsid (teleological) theories of Islamic law by the likes of scholars such as imām al-Shatibi.

2. Ḥasan Ḥadīth

Lastly, when one insists on accepting nothing short of ṣaḥīḥ Ḥadīth, it implies the non-acceptance of another category of Ḥadīth, which is below the ṣaḥīḥ in authenticity, although is still used for purposes of law. This “lower classed” type of Ḥadīth is known as the Ḥasan Ḥadīth.

Is This Really Relevant?

Yes. This subject is relevant since if it was only ‘a few brothers in the mosque’ adopting such an attitude it could easily be avoided or changed. Yet it is worrying when one tunes into Islamic channels to find ‘accepted scholars’ pushing this line of thinking, helping to create a culture of narrow-mindedness and bigotry. It is not surprising that some of the masses are adopting this very attitude. So one is left to think that the TV scholar’s is the only authentic opinion, and the rest are baseless or weak. But this has many negative sociological problems, from breaking the unity in the mosque, to causing rifts within the family, and eventually creating a community at war with each other. Ultimately it means the Muslim community becomes what Prophet Ibrahim supplicated against: from becoming “a fitna21 for the Non-Muslims” (Qur’ān, 60:5) as their social discord projects Islam as a backward and intolerant faith.

If one hears someone adopting such an attitude it may help to remain cautious, ask them if there is a difference of opinion on the matter, and the basis of such a difference. One may also want to ask another scholar of a different orientation in order to maintain a balance and not become a fanatic (muta’aṣṣib).

Conclusion

The purpose of this short paper was not to attack specific members of the Muslim community or specific groups. It was rather to highlight an unhealthy trend that breeds a culture of intolerance. Finally it was to highlight and emphasise the fact that legal differences in dhannī matters are part and parcel of Islam, and simply insisting on following ṣaḥīḥ Ḥadīth will not decrease this. The jurists of the past and present, either directly or indirectly, ultimately base their understandings on the Qur’ān and Sunnah, hence it is nothing short of self-delusional to think it’s the luxury of a few individuals in exclusion to the rest.

- See the fatwa issued by the European Council for Fatwa and Research (ECFR). ↩

- This is according to those who hold that there is only one correct opinion with Allah, and the jurist, through his interpretive efforts, seeks to expose this opinion. If they achieve this, then the jurist gets two rewards, and if the jurist errors and arrives at a conclusion/ruling contrary to what is with Allah, he gets one reward for trying. There is however a difference of opinion on this matter. ↩

- The fact that Fiqh is human and not divine is something that is accepted by scholars and jurists without dispute, and is mentioned by several scholars. ↩

- The books of Fiqh often claim consensus in many areas, although there is a clear difference of opinion. This is probably because the scholar who claims it is unaware of the difference that exists or does not want to give any credibility to the scholarly differences that exists and hence disregards the difference and claims a consensus all in a bid to add more authority to a given opinion, which he (almost always a male scholar) usually follows. ↩

- Muhammad Ibn Hazm. al-Iḥkām.fī Uṣūl al-Aḥkām. 8 vols. (Beirut: Dār al-Āfāq al-Jadīda, no date) Vol. 4, pp.128-143. ↩

- Ibn Hazm. Marātib al-Ijmā’. 3rd Ed. (Beirut: Dār al-Āfāq al-Jadīda. 1982). ↩

- Ahmad Ibn Taymiyyah. Naqd Marātib al-Ijmā’ (Beirut: Dār al-Fikr. 1988). ↩

- Perhaps in another article actual examples can be analysed indicating how even authentic texts have given rise to a difference of opinion. ↩

- Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhāri & Muslim. For an explanation, see my article “Islamic Law: Between ‘Selecting’ and ‘Negating’ a Position”. ↩

- Ibn Taymiyya. Raf’ al-Malām ‘an al-A’imma al-A’lām (Riyadh: al-Ri’āsa al-Āmma li Idārāt al-Buhūth al-‘Ilmiyya wa al-Iftā’ wa al-Da’wā wa al-Irshād. 1983). ↩

- Ibn Hazm. Al-Iḥkām. Vol. 4. Pgs. 132-3. ↩

- Ibn Qudāma al-Maqdisī. Mukhtasar Minhāj al-Qāsidīn. (Damascus: Maktaba Dār al-Bayān. 1978) pg. 127. Similarly other prominent scholars are said to have made similar statements including the righteous leader Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz, Imāms Malik, Ahmad, Sufyan al-Thawri, al-Nawawi. Ibn Taymiyya, may Allah reward them all. ↩

- See al-Ashbāh wa al-Naẓâ’ir of both Imām Ibn Nujaym (Hanaf ī) and Imām Suyuti (Shāfi’ī). ↩

- This list is not exclusive but simply highlights some significant points. ↩

- This can be noticed, especially on TV programs, where some scholars and students constantly emphasis the “ṣaḥīḥ” aspect of the Prophetic tradition they are basing their ruling on to the point of giving the impression that those who differ with them must surely be following a weak opinion or worse their whim. ↩

- This usually indicates an absence or a lack of critical studies of the foundations of Islamic law (uṣul). ↩

- Ibn Taymiyya. Raf’ al-Malām. ↩

- The point here is not whether one must follow one madhab in all issues, but about identifying the scholarly understanding one is basing his/her action on. ↩

- Other attempts at making one’s opinion seem as if it is the only correct view is the inaccurate claim of a consensus, when in actual fact, there isn’t any. ↩

- This does not mean that the texts of the four Sunni schools of thought are free of bias and any other text belonging to another necessarily has a bias. The point is that, whilst the texts of the four schools of thought usually admit their orientation and hence possible bias, texts which claim to fully represent ‘the Sunnah’ do not admit this, and hence run the risk of misleading the reader by giving the impression that its word if final, and any difference existing is invalid or baseless. Thus when a Mālikī text, for example, states that x is Sunnah or preferred, the reader is aware that this is the Mālikī understanding and hence will not be taken aback with the presence of another scholarly understanding on the same issue. ↩

- This word has many denotations. In this context it can mean a cause of suffering. ↩

I lol’d when I read the title, as I knew what was coming next. The people who claim to the title exist in every mosque.

An incident that happened at my mosque was a brother finished his Asr prayer, then after the prayer raised his hands and was making dua. The “Quran and Sunnah” brother came over and informed him that the best time to make dua is in sujood and that the Prophet (saw) didn’t make dua after prayer and that this is bid’aaaa.

I don’t think your analogy fits with Sh. Haq’s legitimate point dear Br. Bilal and Allah knows best. There are many Muslims from the subcontinent who pass up on the clear established practice of the Prophet after every prayer to make some supplication with their hands raised which in this place isn’t the place. often times this supposed supplication is completed in Guiness book time as they are seemingly just raising their hands to wipe their face. This is an innovation which snubs divinely revealed and structured spirituality.

Of course, any reasonable student of knowledge knows that if every now and then someone decided to make Du’a at this time- and it would be better after the athkaar- then it would be perfectly acceptable raising hands or not/wiping face or not.

As,

It is important to note that those who raise their hands do so based on sound evidences and principles. Thus, it should not be labeled as innovation.

Sh. Abul Fattah Abu Ghuda (ra) edited a few important essays on this subject that show this to be a difference over the understanding of sound texts that are open for interpretation.

Declarations of innovation are certainly not befitting one who refers to himself as a student.

Allah knows best

Suhaib

Salams ya shaikh,

Notice the last part of my statement

“Of course, any reasonable student of knowledge knows that if every now and then someone decided to make Du’a at this time- and it would be better after the athkaar- then it would be perfectly acceptable raising hands or not/wiping face or not.”

The innovation is to regularly pass up the legislated sunnah of remembrance after prayer for a general supplication. By the way as I mentioned it is perfectly fine to raise your hand in dua as the Prophet did many times, but in all the narrations about the athkar after prayer we have no narration from anyone about raising hands from the prophet or his companions at this time. Allah knows best 🙂

if we look at the issue closely the mindset is more of madhab dogma- so a hanafi-bred muslim tend to think those who do ibada’ non hanafi way are doing it incorrectly.

please don’t label them as hadith-sunnah.

hadith sunnah people basic tool akal, not emotion or dogma. even PAS in malaysia claim ahlusunnah waljamaah but ‘westminsterised’ Islam by stripping of adab in political behaviour, and claiming sunnah allows that

wow! brilliant article mashAllah. It touches on an important issue with incredible clarity and accessbility. thank you!

This article reminds me of a group of brothers that we have in my area that go by the name “Strictly Sunnah Boyz”….

Solid bro! JAK

The text on this website is far too small, I would suggest you increase it.

Excellent article.

As salaamu alaykum Jameela Al-Bakhnuti.

First off, thanks to everyone at Suhaibwebb.com.

Jameela, you can probably increase the text size from your browser. If you’re using IE or Firefox try holding down the CRTL key and then pressing “+”.

Hope that helps.-

Ma’a salama,

-Jessica Rugg

I remember Sheikh Suhaib had a very poignant and concise experience based around this topic in an Alexandrian taxi cab once.

If the virtualmosque.com staff can dig that out that post for us that would be great. I think it’s a very short and sweet lesson that we can learn from. I tried looking for it once on the site but couldn’t find it.

dear br. webb,

this means then there is no certainty.. Quran and Hadith’s clear laws represent maybe 5-10% of the entire sunnah. Rest is vague. Scholars have spent entire lifetimes’ can not agree then how can we?

I think the point is clear, that the issues is those brothers who say “we want to follow Quran and Sunnah ONLY!” As if our scholarly traditions are a joke or something. Every hadith we read has been discussed, analyzed, and compared with other Hadiths about the same subject for centuries by scholars so great that there isn’t ONE like him in our lifetime. Should we act like their efforts mean nothing? و الـلـه المـسـتـعــــان

We had a “quran and sunnah” society on campus and many students felt with a name like that it must be authentic. Indeed stamping Q&S into the conversation not just gives one the moral high ground from which a selectively narrow interpretation of Islam can be projected, but it really undermines and mocks every other valid opinion which is of course sourced from an interpretation of the Q&S anyway (just not theirs)!

It’s almost like saying “your understanding is based on something other than Islam” and in my humble opinion is the worst insult you can give your muslim brother / sister. It’s just another effort to monopolise the religion

Salam

Its same old maqasid/usooli rhetoric that we have unfortunately become used to. I for have never heard a person just using quran and h without relying upon scholars. They existed long time ago but in this day and age…an elderly respected board member would not just rebuke you without wisdom. Perhaps the source of income you were mentioning for the masjid wasn’t really legit? Maybe this brother does not want to stand on yawmul qiyamah and answer his Rabb about how he used his authority unislamically (albeit you might not think that). You can find scholars giving a halal verdict to everything under the son. Why would you feel sorry for someone if he filters those fatawa out. You know with all this bashing you guys are doing to these ignorant/wisdom lacking/non-usooli brothers of yours…I fear you might end up being a victim of arrogance yourselves? perhaps some brothers do think that maslaha should be first judged in the light of quran and sunnah unlike how some are applying these days? we have khateeb these days giving series of lectures on maqasid to people, in mass khutbahs, when some of the jumuah audience doubts even basic pillars of Islam. I do not see what objective this new culture of du’at are trying to bring…just showing off their sophistication and knowledge and perhaps…why they should be the ones that “define American Islam”? May Allah guide us to the straight path and really put His fear in our heart for how we guide people. Allah will not unchain a persons feet on yawmul qiyamah if he has 10 or more people under his authority….just think of your followers before you post.

Please forgive me for being out of my place to give naseehah…and forgive me if I am mistaken

Your brother in islam

Asalamu’alykum,

Dear ‘brother’,

The article is not about the brother in the mosque, who is not an elderly person btw. I never doubted the sincerity of the brother, but his “DIY” method was something that alarmed me. Sincerity is good, but sincerity alone is not enough to validate an incorrect method. After that incident, I have heard of others who have also reported similar things from him (which I don’t want to mention here as this article is not about him), but the point is, if you read the last paragraph, this article wasn’t just based on one experience, it was based on a lot of interaction with brothers and scholars. And where dear brother, do we “bash” people? I find it alarming that you percieve advice and education as something that is seen to be bashing? I also find it saddening brother that you find articles on this site as a mere excercise of “showing off knowledge” Perhaps you could enlighten as to how you know the intentions and motivations behind people’s actions?

Dear A Brother,

Assalamu Alaikum. It seems that perhaps more was read into this article, and the direction of this website than is truly there.

There is absolutely no doubt that the Quran and the Sunnah are the source of guidance of our lives, our commands, our prohibitions, and everything else from our births to our deaths.

The sophistication that has been presented is not show off – it is a confirmation of faith that the Deen of Allah (swt) and the message of Our Prophet (saw) has been preserved and that it has the ability to provide guidance in all circumstances – these are not made up words, but how the Islamic legal system actually works. It is an attempt at educational literacy, not at bashing, and you will see that articles on this website never attack personalities, groups, or people, but focus on ideas and concepts.

Lastly – you are correct that there are many instances where what the community needs, is not being given to them. Instead, they may receive speech on topics that are unrelated to their issues. This website caters to a very broad audience – students of knowledge, community members, parents, teens, converts, youth, and leaders. So the site aims to try and ensure everyone gets some good that they can benefit from. This is why you will see some articles about the legal mechanisms within Fiqh, some about spirituality, some about difficulties faced by converts and so on.

I hope inshAllah that Br. Haq’s comment and this one, put to rest some of your concerns.

wa alaikum assalam

Abdul Sattar

Assalaamu Alaikum, Brother, thank you for raising your points. It is true that many people are apt to dismiss the viewpoints of others.

Boiling it down, this all started from an encounter in which there was some disrespect. Your viewpoint wasn’t taken in terms of the fundraising, and you didn’t appreciate the manner in which your opinion was excluded. The brother did seem to cut you off rather abruptly, and he used a tagline or slogan “Quran and sunnah” to shut you down in the conversation.

I think this is more about hurt feelings and a bad turn in the conversation than about now labeling anybody who uses the term Quran and Sunnah.

The brother hurt you (your honor) more than I think he realized. Rather than write articles about these kinds of interactions, it could be more productive to sit down with the brother and just say, “You know, I felt disrespected and cut off in the conversation.” Maybe another brother could make islah between you.

By your invoking his call for “quran and sunnah” and kind of degrading it (and the phrase and meaning are noble and should not be degraded) – even though you make a good point in terms of the need to respect the scholars who also have made their rulings based on Q and S – it just seems like you are avoiding the real human interaction that occurred, kind of blowing it up into a big philosophical deal, and forgetting the real person you were dealing with.

The brother is older, and is due respect for that alone. He is usually calm as you say, and it seems he flew off the handle a bit in that particular circumstance. Maybe he didn’t mean to imply all those things you think he did. You could try going to your brother in Islam and working it out.

May Allah swt reconcile your hearts on what pleases Him. Ameen.

I do agree, that it feels like the writer has been hurt.

Asalamu’aykum,

JazakAllahu khair for your advice, but to suggest that the point of this article is to somehow vent my anger means you’ve really missed the point. If you read the article, I mentioned that I did not write it as a result of some issue I had with the brother. Please have some good opinion of your brother, do you think I will write a whole article so that I can take “revenge” on some brother who I didn’t even mention? Allahu Akbar…May Allah purify our intentions and actions. I had noticed this trend a while back, had many encounters, and this anecdote regarding the brother was just to highlight how equating human cognition (fiqh) to the shari text in issues wherein the sources are obscure is so rampant such that people think it is a mark of their religiosity to be firm and definitive in every issue they study. There is no argument/hard feelings between us. Please offer some constructive feedback, if you may, on the topic of the article, and not on some tangent.

May Allah protect us from the evil of ourselves.

Haq.

I hope not, my dear brother, but I reads like it. Outside the part of the article its usefull and practical, but not an end.

It’s much easier to believe in the Quran and authentic hadith without to seclude the opinions of the old scholars of the mathab.

Wow. Well, I did not say you were trying to get “revenge” on the brother – never used that word and never thought it – or that this was an exercise in venting your anger.

I do think it is constructive to encourage folks, if and when they hear their brothers saying “we only follow the Quran and Sunnah” or a similar phrase, to question whether it necessarily means the speaker is intolerant, bigoted, ignorant of fiqh issues, or trying to say that everyone else is “doomed”.

Maybe you are making a purely intellectual argument that has no practical application in every day life interactions. However, I think the relevance of your article is in how these issues get played out in real life in the real interactions of real muslims.

A culture of intolerance — The only “so what?” of that is how it hurts people’s feelings and honor, how it disrespects them, how it does make them angry (that is not a dirty word; we are not robots), and how it makes the relationships between brothers in Islam (and sisters) less than they could be.

Looking at these interactions in holistic ways, grounded in the reality of individuals interacting, acknowledging the emotions and complexity of motives, is healthy, in my opinion anyway. I think this is part of fostering a culture of tolerance. You may not agree with taking this approach, but I think it is at least to the point. At least, to the larger point.

Anyway, I’m sorry if I insulted you. I did enjoy your article, it is well written, and I did appreciate many of your points about the breadth of fiqh, and how narrow-mindedness creeps into discourse.

I’m not trying to minimize all the thought and research that went into your article, I kind of fast-forwarded to the practical, emotional impact – impact exemplified in your opening anecdote.

Salaams,

Firstly, it’s ok I wasn’t insulted just wanted to make sure it didn’t seem as if the purpose of this article was a personal vendetta against a brother, JAK for clarifying. I agree with you with regards to how intolerance can affect relationships (which we can categorise under the title “harmful effects of intolerance”). This is definitely something important to consider, as it breaks up the unity of the Muslims which Sheikh al-Islam Ibn Taymiyya called such a person “an innovator”. The purpose of this article was to focus on the cause of such intolerance not the effects (although maybe that deserves another piece). What worries me more is the fact that intolerance eventually leads to the culture of calling each other innovators, “people of desire”, and even worse disbelievers based on matters of dispute. Just to give you an example, I’ve heard an individual, who is accepted as a scholar; say how Imam Ghazzali and the likes are worst than the Christians (wal ‘iyadhu billah) with regards to a specific statement of his which this individual probably has misunderstood.. Now I find it worrying to realise the effects of such teachings on a community. The culture of Takfir (calling people disbelievers) is also used by those who want to make mass murder of innocent people permissible (the logic is: since they were Muslims, now they are “disbelievers”, their blood has become lawful). People also base their al-wala and al-bara on such issues, which, as Ibn Taymiyya states, if incorrect (again splits the community, and this historical proof). However there are harmful effects to the individual himself/herself, such as a person who makes takfir of others without it being valid is himself/herself rendered a disbeliever.

Lastly, you’re probably right that the brother, and others like him, don’t think this deep about the implications of this intolerance, but their inattention, unfortunately does not afford us the protection against the harms of such an attitude.

May Allah bless you and me and increase us in good.

Haq.

Some of the comments are interesting to say the least. JazakAllahu khairan for the article. I have also been puzzled by the clinging to Fiqh-us-Sunnah. I think you said in a previous article or comment on this site, that some have left their madhhab and become muqallid of Imam Sabiq (May Allah have mercy on him), subhanAllah.

Is there a plan to synthesize the various articles (Shaikha Muslema’s translation of a portion of Shaikh Qaradawi’s work, the six mistakes in usul, this article and other related ones) into a cogent approach for the laymen?

wassalam,

Jeremiah

As-salamu ‘alaykum,

A very useful article. The diagram will help visual learners to realise there is a difference between Shari’ah (the totality of revelation) and fiqh (scholarly attempts to understand that revelation).

@ Student. There is a principle that one should not condemn when there is ihktilaf. The greatest scholars rarely, if ever, condemn, because they have so much knowledge of different scholarly opinions that they can usually find an excuse. Unless one has mastered a particular issue one should either ask or remain silent.

This is a tremendous article. You must continue to spread this type of thinking. The Muslims will always be weak until we implement the proper ethics of disagreement.

“And hold firmly to the rope of Allah all together and do not become divided. And remember the favor of Allah upon you – when you were enemies and He brought your hearts together and you became, by His favor, brothers. And you were on the edge of a pit of the Fire, and He saved you from it. Thus does Allah make clear to you His verses that you may be guided.” (Surat Ali Imran 3:103)

As a youth I was taught the sources of Islamic law and I understand it’s not as simple as, “Quran and Sunnah,” because as you have explained, not all issues are covered by the primary sources, and even when they are there is the matter of interpretation.

But, without knowing the intentions of the brother mentioned in the article, I can say that I have also come across this attitude, and that often it stems from a mistrust of modern scholars. There is a perception among some people that many scholars are bought and paid for, and will render almost anything halal upon demand. There are other scholars who follow deviant paths and espouse all kinds of bizarre teachings. So there are people in the community who, as soon as they hear the phrase, “the scholars”, react emotionally and reject everything that follows.

In a similar vein, some people are Islamically uneducated and don’t know who to trust. One person comes to them one day and says, “You should do it this way,” and another person comes and says, “Do it that way,” so their reaction is, “I don’t trust any of you or your so-called scholars”, I will just stick to Quran and Sunnah.

That in itself leads to arguments, as you then get individuals who imagine they can read Saheeh Al-Bukhari and derive a ruling from a single hadith.

I don’t really have a solution, aside from the suggestion that basic Islamic education courses should be offered at all masjids, and all should be encouraged to attend.

As salaamu alaikum wa rahmatullah

Just to comment on the claim that ‘No one can condemn another for holding a valid view.There is no inkār (rebuking) in matters of ikhtilāf.’

The issue of a ‘view’ being ‘valid’ has to be determined by something. There has to be recourse in differing. The recourse is to refer it back to Allah and His messenger. Albeit the brother’s understanding of that may be clouded but on the flip side the above mentioned principle is also a misunderstanding. It is definately a contended principle. An elementary reading of the lives of the sahaba would show that they did make inkar on people/opinions that they felt went against the evidences and proofs (an entire book was written about Aisha’s differing with other sahaba). The famous quote from Ibn ‘Abbas illustrates this point. “Maybe a stone will be sent down upon you from the skys. I say that the Prophet (sallahu ‘alaihi wa salam) said something and you say Abu Bakr or Umar said something else.” Or Imam Ahmad’s famous quote, “I’m baffled by a people who know the strength of a a chain narration and then leave it for the opinion of at Thawri.’ In Ibn Abbas’s statement there is a definate inkar of putting the sayings of the two most illustrious personalities in Islam after the Prophets above the satement of the Prophet (sallahu ‘alaihi wa salam). He didn’t just say ‘Okay,al hamdulillah. They have they’re proofs. I’ll just leave it at that.’ Also, when Ibn Mas’ud learned that Uthman didn’t shorten the prayer while traveling, he said, “Inna Lillahi wa inna ilayhi raaji’oon.” This is definately a verbal inkar even though Uthman was more knowledgeable and also the khalifah (who we’ve been commanded to follow). He didn’t just leave it at ‘okay he’s more knwledgeable then me so I’ll follow him his opinion is legitimate.’ Of course Ibn Mas’ood recognized his position and followed him and made his famous saying, “Al Khilaaf shar (Differing is evil).” These are limited examples of the sahabah making inkar on opinions and actions they thought went against stronger proofs and evidences.

It would have been nice to see the author research the issue more with regards to the Ulama who reject this statement, like Ibn Taymiya, Ibn Al Qayyim, As Shawkani, and others.

Sheikh Ul Islam Ibn Taymiya said in regards to the misnomer ‘La inkar fi masaail khilaaf’, “This is not correct. Rather the inkar is directed to either the saying of a particular ruling or directed towards acting upon it. In regards to the first issue, if a saying contradicts the sunna or ijmaa qadeeman (ijmaa from the 1st generation as Ibn taymiya saw legitimate ijmaa as being from the sahabah only) then it is an obligation to make inkaar. And if it isn’t like this, then inkar is made by explaining the weakness of the statement according to those scholars who see the correct position as one and they are the general body of the salaf and jurists.With regards to actions, if they are contradictory to the sunna or ijmaa, then they too are to be rejected (by making inkaar) in accordance to the different levels of inkaar. However, if the issue at hand has no (precedence in the) sunna or Ijmaa’ and it is an issue in which ijtihaad can be used, then there is no inkaar made upon the person who acts on it whether he be a muqallid or mujtahid. The reason for misunderstanding on this issue is because the person (who adopts this maxim) incorrectly believes that masaa’il ikhtilaaf are masaa’il ijtihaad The correct position of which the Imams are upon is that masaa’il ijtihad are those affairs in which there is no evidence/proof which obligates one to act upon it in the sense of it being an apparent obligation (wojoob dhaahiran) like a sahih hadith which has no other related hadith (seemingly) contradicting it. So it is permissible to make ijtihaad if it lacks this definitive text or because of related (seemingly) contadictory texts or if an issue has no determining textual evidence.

In regards to this misnomer that ‘there is no inkaar in matters of ikhtilaaf’. Imam al Shawkani states, “This principle has become the greatest means to closing the door of enjoining the good and forbidding the evil…… The criterion for affairs is the Book and the Sunna. It is an obligation for every muslim to command to that good which he finds in them (the Book and the Sunna) or one of them and to forbid from that evil which has been explicated in them or one of them. And if a scholar makes a statement which contradicts that then his statement is a munkar that must be rejected first and foremost and then inkaar is to be made upon those who act upon this incorrect statement.”

One can find these statements in the following books Bayyan Ad daleel fi Ibtaal at Tahleel, Ibn Taymiya (pg 210), I’laam al Muwaq’een Ibn Qayyim (3, 300) and Sayl Al Jaraar from As Shawkani (4, 588).

Also another example of scholars who rejeced this notion is the saying of Sheikh ul Islam Abu Isma’eel Al Ansaari Al harari who said (in Ibn Hajrs Tadhkera), “I’ve been threatened with the sword 5 times and it was never said to me ‘leave your madhab’ rather it was said to me ‘Be quiet in regards to those who differ with you.’ My reponse was, ‘I won’t be quiet.’

Assalāmu `alaykum wa raḥmatullāhi wa barakātuh,

Dear brother Mohd. Nur, I would like to address the issues that you have raised in your comment. I pray that Allah guides us all to what pleases Him.

I believe the content of your post can be summed up in the following three points:

A. The only way to establish whether an opinion is valid or not is to refer back to Allah and His Messenger (may Allah bless him and grant him peace).

B. The Companions used to make inkār of those whose practices they felt were going against textual evidence.

C. The stated axiom is contended by the likes of Ibn Taymiyya, Ibn al-Qayyim, Shawkānī, and others.

Here is my response, may Allah grant me the ability to articulate it clearly:

A. I agree that the issue of a view being ‘valid’ has to be determined by something. However, the recourse that you mentioned, namely to refer back to Allah and His Messenger (may Allah bless him and grant him peace) is the recourse of the experts – namely, religious scholars and advanced students of sacred knowledge. As for the layman, he only needs to look at the credentials of the one who espouses that opinion in order to determine its validity. An opinion that is held by a reputable mujtahid, whose authority is agreed upon by the corpus of Muslim scholars, is ‘valid’ as far as the layman is concerned, especially when such an opinion is held by one or more of the four schools. As Imām Shāṭibī said in his Muwāfaqāt, “The formal legal opinions [fatāwā] of qualified scholars work for laypeople in the same way that textual evidences work for scholars.”

B. You mentioned three incidents from the lives of the early community [salaf] to show that they made inkār of those whose practices they felt were going against textual evidence. I would like to address each of them one by one:

1. The first quote you mentioned was from Ibn ʿAbbās. According to you, he said, “Maybe a stone will be sent down upon you from the skys [sic]. I say that the Prophet (sallahu ‘alaihi wa salam) said something and you say Abu Bakr or Umar said something else.”

First, it would be useful to mention the context in which this statement was made. Ibn al-Qayyim cites three different reports for this incident in Zād al-Maʿād, two of which contain a response from ʿUrwa after Ibn ʿAbbās made the statement that you mentioned. Here is the full story:

ʿAbdullāh b. ʿAbbās was telling people to perform tamattuʿ (a type of Ḥajj where one performs ʿUmra before performing Ḥajj). ʿUrwa b. Zubayr (the tābiʿī scholar who was the nephew of ʿĀ’isha bt. Abū Bakr, and the son of Zubayr b. al-ʿAwwām and Asmāʾ bt. Abū Bakr) learned of this, he confronted Ibn ʿAbbās and said, “Are you telling people to perform tamattuʿ in these ten days (of Dhul Ḥijja)? Don’t you know that no one should perform ʿUmra in these ten days?” Ibn ʿAbbās replied, “Why don’t you go and ask your mother (Asmāʾ) about this?” ʿUrwa said, “Abū Bakr and ʿUmar prohibited people from doing this.” Ibn ʿAbbās replied, “By Allah, I don’t think you will stop (behaving in this way) until Allah sends down His punishment on you. I narrate to you from the Messenger of Allah (may Allah bless him and grant him peace), and you tell me Abū Bakr and ʿUmar said such and such?” At this ʿUrwa said, “I swear by Allah that they were both more knowledgeable regarding the Sunna of the Messenger of Allah (may Allah bless him and grant him peace) than you!” At this, Ibn ʿAbbās became quiet.

From this, we note the following:

a. Ibn ʿAbbās was speaking to ʿUrwa, who was one of the greatest scholars (of ḥadīth and fiqh) of the second generation of Muslims. He was not speaking to a layman! As I pointed out earlier, the scholar must refer back to the Qurʾān and Sunna when faced with different opinions, but the layman is not required to do that; he may follow any ‘valid’ opinion from among the various juristic opinions.

b. Ibn ʿAbbās did not rebuke ʿUrwa for doing something on which there is scholarly disagreement. He rebuked him specifically for giving preference to the practice of Abū Bakr and ʿUmar over the practice of the Prophet (may Allah bless him and grant him peace).

c. ʿUrwa provided his reasoning. His response implied that he was not giving preference to the practice of Abū Bakr and ʿUmar over the practice of the Prophet (may Allah bless him and grant him peace), but he was not convinced that Ibn ʿAbbās had interpreted the Sunna correctly in light of the practice of the two Caliphs, who were more knowledgeable of the Sunna than him.

Ibn al-Qayyim goes on to show that it was actually ʿUrwa who had misunderstood the practice of Abū Bakr and ʿUmar. In fact, they had never prohibited people from performing tamattuʿ, but only discouraged them from doing so, and encouraged that they perform ifrād (a type of Ḥajj where one performs Ḥajj first, and then performs ʿUmra after it) instead. So in fact, there was no contradiction between the teaching of Ibn ʿAbbās and the teaching of Abū Bakr and ʿUmar.

2. The second quote you mentioned was from Imām Aḥmad. According to you, he said, “I’m baffled by a people who know the strength of a a [sic] chain narration and then leave it for the opinion of at Thawrī.” I would like to point out two things regarding this quote:

a. Imām Aḥmad’s criticism is directed towards those who prefer the opinion of Thawrī, even when they contradict the teaching of a ḥadīth which they know to be authentic. There is no dispute about this! Anyone who knows with certainty (or ghalaba al-ẓann, to be exact) that the Prophet (may Allah bless him and grant him peace) taught something is not permitted to follow an opinion that goes against it, no matter who holds such an opinion. Therefore, this is an example of Imām Aḥmad doing inkār of an act which contravenes something that is agreed upon. He is not doing inkār of something on which there is scholarly disagreement. Recall that the axiom states, “There is no inkār in matters of ikhtilāf.” As for those things that are wrong by consensus, one must do inkār of them, of course, following the guidelines of al-ʾamru bil-maʿruf wa al-nahī ʿan al-munkar.

b. It is obvious from the statement of Imām Aḥmad that he was speaking about experts, and not laypeople, for he said, “people who know the strength of a chain narration.” He is clearly speaking about those who have the ability to authenticate Prophetic reports, and extract rulings from them, which is the realm of the mujtahid. For such a person, it is not permissible, according to the vast majority of Uṣūliyyūn, to do taqlīd of anyone. Instead, such a person must do what his ijtihād leads him to. Therefore, Imām Aḥmad’s inkār here is directed towards those who have the ability to authenticate reports and derive rulings from them, and yet suffice themselves with taqlīd, not laypeople.

3. The third quote you mentioned was from ʿAbdullāh b. Masʿūd. This incident was reported by Bukhārī, Muslim, and others, on the authority of ʿAbdul Raḥmān b. Yazīd, who said, “When ʿUthmān [b. ʿAffān] led us in prayer at Minā, he performed four rakʿāt. When ʿAbdullāh b. Masʿūd was asked about this, he said, ‘Innā lillāhi wa innā ilayhi rāji`ūn [To Allah we belong, and to Him is our return]!’ Ibn Masʿūd said further, ‘I prayed at Minā behind Allah’s Messenger (may Allah bless him and grant him peace), Abū Bakr and ʿUmar – all of them performed two rakʿāt.'” He then remarked, “I hope Allah accepts my four rakʿāt as two.”

You commented about this incident saying, “This is definately [sic] a verbal inkar even though Uthman was more knowledgeable and also the khalifah (who we’ve been commanded to follow). He didn’t just leave it at ‘okay he’s more knwledgeable then me so I’ll follow him his opinion is legitimate.’

Before I respond, I think it would be useful to look at what Imām Nawawī says in Sharh Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim, commenting on this ḥadīth. He says, “The meaning of what Ibn Masʿūd said [at the end of the ḥadīth] is, ‘I wish ʿUthmān had performed two rakʿāt like the Prophet (may Allah bless him and grant him peace), Abū Bakr, `Umar, and `Uthman himself used to do at the beginning of his caliphate.’ The intent of Ibn Mas`ud was to show his dislike [karāha] for contravening the practice of the Prophet (may Allah bless him and grant him peace), and his two Companions (Abū Bakr and ʿUmar). Despite this, however, Ibn Masʿūd agreed that it is permissible to perform four rakʿāt. This is why he used to perform four rakʿāt himself when praying behind `Uthman. If shortening the prayer was obligatory [wājib] in his opinion, he would not have considered it permissible to leave it, regardless of who he was praying behind. As for the fact that he responded by saying innā lillāhi wa innā ilayhi rāji`ūn, he meant to show his dislike for not doing what was superior.”

In light of this, I would like to highlight a few things:

a. Ibn Masʿūd did not believe that ʿUthmān had done something wrong [munkar]. He simply believed that he had done something that was less superior, while shortening the prayer would have been the better thing to do.

b. The axiom states that there is no inkār in matters of ikhtilāf. The word inkār in the Arabic language means ‘to renounce, reject, censure, or reproach.’ It does not mean to disagree with. It is a stretch to say that Ibn Masʿūd saying innā lillāhi wa innā ilayhi rāji`ūn amounts to inkār. How so, when what ʿUthmān did was not munkar to begin with? Ibn Masʿūd was doing nothing more than expressing disagreement with what ʿUthmān had done, because he believed the better thing to do would be to shorten the prayer. According to the axiom, it is not permissible to do inkār of matters on which there is ikhtilāf, but obviously one may respectfully disagree with them, that’s why they are called matters of ikhtilāf!

c. The fact that Ibn Masʿūd ‘didn’t just leave it as ‘okay’ he’s more knwledgeable [sic] then [sic] me so I’ll follow him his opinion is legitimate’ is because he is a mujtahid, not a layman. As I mentioned before, it is not permissible for a mujtahid to do taqlīd of anyone. Therefore, when someone asked Ibn Masʿūd about the issue, he responded according to his own ijtihād. The case of the layman is different, as I have already clarified.

d. This incident, in fact, is an excellent example of mutual respect that existed between the Companions. Their disagreements did not lead them to condemning each other, rebuking each other, or attacking each other. It did not lead to mutual discord, where everyone claims to be on the truth, and accuses his opponent to be on falsehood, committing bidʿa, and being in opposition to the Qurʾān and the Sunna. Ibn Masʿūd did none of that. He quietly prayed behind ʿUthmān until someone asked him for his opinion, at which point he expressed it to him privately, without using even a word of disrespect towards ʿUthmān, who certainly had the right to follow his own ijtihād on the matter.

As for the book about ʿĀʾisha differing with other Companions, I reiterate: there is no problem when a qualified scholar disagrees with another qualified scholar, based on his/her ijtihād. The problem arises when a layman begins to condemn (do inkār of) others who are following a legitimate scholarly opinion. This is what the axiom forbids.

C. The final point you raised was the fact that this axiom is contended by the likes of Ibn Taymiyya, Ibn al-Qayyim, and Shawkānī. To this, I agree, but what exactly is their contention, and what is its consequence?

The contention of Imām Ibn Taymiyya, and Ibn al-Qayyim, is that there are two types of issues on which disagreement might exist. The first type consists of issues that are addressed by definitive, unequivocal [qaṭʿī] texts of the Qurʾān or Sunna. Disagreement in these issues is termed ikhtilāf, which must be rejected, and condemned, because it contravenes a qaṭʿī text from the Qurʾān, Sunna, or ijmāʿ [scholarly consensus]. The second type consists of issues that are either not addressed by the sacred texts at all, or addressed by texts that are probabilistic [ẓannī], and therefore open to ijtihād, i.e. more than one scholarly interpretation. With respect to these issues, disagreement is to be expected, tolerated, and respected. This is the essence of Ibn Taymiyya’s distinction between masā’il al-ikhtilāf versus masā’ilal- ijtihād, as expressed in the passage you mentioned, if you read his words carefully.

It should be noted that none of this contradicts what Ust. Haq has written in his article. If you look at his article again, he alludes to this distinction towards the beginning, under the sections titled, “One Understanding” and “Many Understandings.”

I strongly suggest that you look at Dr. Qaraḍāwī’s book, Kayfa Nataʿāmalu maʿa al-Turāth, pp. 154-162, where he discusses this axiom at length. Alḥamdulillāh, the first half of this section was actually translated for this blog some time ago by Ust. Jamaal Diwan, and you can read it here:

http://www.virtualmosque.com/islam-studies/no-condemnation-in-areas-of-ijtihad/

The second half of the section, however, which has not been translated, is where Dr. Qaraḍāwī reproduces the same passage of Ibn Taymiyya from Iʿlām al-Muwaqqiʿīn that you have provided in your comment, and discusses it in detail.

As for Shawkānī, his words must be understood in light of his anomalous position regarding taqlīd. It is well known that Shawkānī, like Ibn Ḥazm, considered it unlawful for anyone to perform taqlīd. Instead, he believed it was obligatory upon every Muslim, including laypeople, to perform their own ijtihād. He strongly championed this idea in many of his books, including Irshād al-Fuḥūl, al-Sayl al-Jarār, and al-Qawl al-Mufīd fi al-Ijtihād wa al-Taqlīd. For a thorough discussion of his views, please see the following article posted by Ust. Muslema Purmul a few weeks ago on this blog:

http://www.virtualmosque.com/islam-studies/islamic-law/taqlid-and-following-a-madhhab-between-absolutism-and-negligence/

To conclude, I believe the following words of Imām Ḥasan al-Bannā provide the most balanced and comprehensive approach to deal with differences in opinion. He said, in his famous Twenty Principles, “The Eighth Principle: Differences in matters of fiqh should never be a cause of division, nor should such differences lead to quarrel and hatred. Every mujtahid is entitled to his reward (from Allah). Nevertheless, there is no harm in conducting objective academic analysis of those issues on which there is juristic disagreement, as long as it is done in the spirit of mutual love for the sake of Allah, and cooperation to reach the truth; it should not lead to blameworthy argumentation and bigotry.”

Wallāhu aʿlam,

Arsalan

salaam,

JazakAllahu khairan for that awesome and detailed response~!

JazzakAllahu Khair Br. Arsalan for your informative and coherent reply!

Bismillah

As-Salaam Alaykum

My question for the author is:

Can you give an example to clarify (for those who didn’t understand ) the statement:

‘“an Ijtihād is not made redundant by another Ijtihād”. This means that such differences will always exist and no amount of insistence on “ṣaḥīḥ Ḥadīth” will help unify them.’

Jizak Allah Khayr

GH

Wa’alykum as-Salam Br. Gabriel,

Firstly, sorry for the late reply. Secondly, about your question, I did think of giving examples in the article but for fear of making it too long, I didn’t. a quick example I could give you is about the six fasts of Shawwal that are recommended after Ramadhan. The Hadith mentions about the time of the fasts “six days from (Arabic: min) Shawwaal” Majority of the scholars understood this to mean six fasts of Shawaal, but Imam Malik understood it to mean “Starting from Shawaal”, hence said these fasts can be kept any time after Ramadan so long as its kept before the next Ramadan. So whilst they agree on the authenticity of the Hadith, they differed n their interpretation.

Hope this helps,

Wassalam

Haq.

Thank you for this important article. May God reward you!

Jazakullah Muhammad:

This is good. What we need is to remove the cancer from the ummah. Some of the cancer is in oour blindly accepting something as a requirment of the deen just because someone says that: “Muhammad 9saws”) said”. but we need to be wiise enough to distinguish what he really did say and do and incorporate that into our lives.

The best way for accomplishing that is by mens of more and more discussion.

Aslamu Alaykum,

I enjoyed your article greatly. I had a quick question, for my better understanding not to argue. In this day and age, we now have access to volumes of information electronically. The scholors are human and only had limited time on earth. If a scholor did not have time in his life to study a particular thing in great detail, like for example “can a woman touch the Quran in her period”. If they just took the previous rulings at face value based on the resources their teachers had and passed it along, then a scholor of today can search all of the Quran, Hadeeth, companion, and scholory opinion about a certain issue. Is it possible that he can find an opinion to be certain now when limited resources and a lack of contestation in the past prevented the in depth study? Thanks. Keep up the good work!

Wasalamu alykum wr,

A very thoughtful question br Yousef. In my opinion, I think it would be very rare for a scholar today to come across a hadith or other piece of evidence that can definitively settle all disputes. This is because for more than 700 years rulings and interpretations have constantly been revised and reviewed by scholars from all different schools of law (madhab) and they are usually referred to as “Muhaqqiqeen” (research scholars). This leaves the chances of finding such strong evidence rare.

Secondly, even if such an evidence was to be found, there is almost always differences in how texts are understood, thus even then there will still be different scholarly interpretations. Nonetheless, it could be, that such evidence if found, can bolster one interpretation and give it more credibility over others. But I think even the chance of that happening is minimal due to different methods employed in interpreting texts.

However what you mentioned did sometimes happen in the very early stages of Islam. For example Uthman (ra) used to hold the opinion that ghusl (bath to ritually clean yourself) was made wajib by a person physically engaging in sexual intercourse. However if a man simply ejaculated through other means, then ghusl was not wajib on him. However due to the hadith which says ghusl is made wajib by ejaculation alone, all the scholars after him, and even during his time differed with him (I’m not aware if later scholars still held the opinion of Sayidina Uthman, but if you do come across any that do, please do let me know).

Now from our perspective, especially with the other scholars differing with Uthman, we know retrospectively that Sayyidina Uthman’s (ra) opinion was actually incorrect. None the less he based it on the evidence that he had, and inshaAllah he will no doubt be rewarded for it.

Can this happen today? I doubt it…

JAK for your contribution

Haq.

It is consistent with a more general phenomena whereby the skill of deriving decisions based on a hierarchy of reasoning, is not common in the general population (I don’t know if this has always been the case for hundreds of years, or from a certain more recent period). In basically any kind of logical discipline, there is such a demand for simplification, that even the tools of reasoning are no longer taught, only the outcome of it. This is analogous to relying solely on calculators or software, without also taking time to learn the algorithms and equations underlying them (or at least what equations are, and in general terms how it produces the result). It is the bane of my professional existence.

The consequence is, people think one factual data or statement has only one interpretation, because that’s what they’re habituated to expect, because the other statements and information that the learned person weighs, not to mention the hierarchy of reasoning that is employed, is invisible to them. It also means, they cannot tell the difference between a poorly derived conclusion, and a well-derived one, and do not realise that in many cases, simply being aware of reasoning methodology is enough to differentiate between really poor/disqualified vs potentially credible arguments, without needing to be an equivalent scholar (although you would need to be for better accuracy than that). Frequently – especially on religious topics – it ends up boiling down to claims of the degree of ‘holiness’ of ‘my scholar vs yours’, usually measured by arguably unrelated traits such as outward appearance, routine commitment to certain acts of worship, popularity, degree of relatedness to own race/country, degree of relatedness to Arabs (the race of the Prophet), and claims of supernatural signs of sainthood. I am highly appreciative of your efforts to restore the original high quality reasoning once considered the norm among the Companions, and which actually was the precursor and set the standard for the standard of reasoning that forms today’s expected norms in all professional disciplines.

A spin-off phenomenon is: the ability of such reasoning is present from advanced schooling, but for some reason certain lay groups believe this is improper to apply it to ‘religious’ topics because it is ‘only for science and other dunya disciplines’, so psychologically they exclude the skill out of taboo feelings.

My 2 cents. I read only a little bit of the article as it went into things that I didn’t care to read on as what I have to say is against the declared position of the author.

No scholar’s opinion is bigger than Quran and ahadith. The Quran clearly says follow Allah and follow the messenger and those amongst you with knowledge. ..and when you differ follow Allah and the messenger. …so Allah is saying in Qurab that at the end you dont even follow scholars if their opinion mo matter how informed goes against the quran and ahadith. ..so there is nothing wrong to say we follow Quran and Sunnah as that is exactly what Allah commands us to do….

Previous comment had typo *Quran and *no

Jazaka Allah Khery Ustad Haq. Wlhi you gave me hope. I thought, the people who thought this way are gone from earth. And only layman’s rule the day. I , like you get tired of this nonsense statement, and I always asked my self as my sheikh said ‘ If Amirul-Mumini fil hadith needs fighi who are we to say we don’t” I, also, wonder if these people understand what they saying because they argue we followed Quran and Sunah and same people who brought Quran and sunah from the prophet SCW and his generations should not be listen to it. So, my question is who informed these people and who told them this hadith is sahih, or weak. In addition every hadith that is out there is known by shafis ,hanafis, maliks and my I say fudalau-Hanabila. And no matter what we do in my humble opinion we would never find out scholars more knowledgeable than our previous scholars. In addition, one comment reads, Madahibs my confuse people and my answer would be Madahibs bring people together. I consider my self Shafici, but I learned in early ages that all Madhabis are haq. So, if I see hanafi brother/sister, I walahi know they are in straight bath, even-though we disagreed in some issues. And that is what preserved Islam and that is the only thing that would preserve Islam in the future. And my Allah gives you extra reword for your work.

We do believe Islam consists of Quran and Sunnah and they are in the same level because there is no conflict between them…the sunnah, which is the way of Mohammed’s (PBUH) life, is the explanation of Qurran..and without it (the Sunnah) Muslims would never know how to translate the Words of Allah (Qurran) to our daily life..