Many of us live busy lives which we often have to compensate for by requiring things done instantly. Of course, the plus side of this is that ‘productivity’ increases, but it undoubtedly comes at a cost, often to our health and/or general lifestyles.

Many of us live busy lives which we often have to compensate for by requiring things done instantly. Of course, the plus side of this is that ‘productivity’ increases, but it undoubtedly comes at a cost, often to our health and/or general lifestyles.

Technology has played a significant role in facilitating this—take email as an example. In the past (which was not so long ago), you would have to write a letter, either by hand or type-written, after which you would post it through the mail. If you posted it earlier enough in the day, your recipients may receive it the same day, otherwise they would get it the next day or later depending on the amount you paid for postage. This whole process is now reduced to simply signing into your email account, writing your letter, and simply pressing ‘send’ and by the magic of technology, your letter is ready and waiting for your recipient instantly.

This instantaneous delivery has also spread to food, which has led to a relative increase in the consumption of fast food to such an extent that some have dubbed us as the ‘fast food generation.’ I am not suggesting that the ‘fast’ aspect of fast food is the only factor driving people to consume it, but it is reasonable to consider it as a significant contributing factor. Of course, putting aside all the good that may result as a consequence of this, as critical thinkers and conscious beings, it behoves us to stop for a moment and think about the negative consequences too, and one in particular: Instant gratification.

Instant gratification, as the name suggests, is when we want immediate rewards for something we do. It is connected with our appetites (nafs). In Arabic, it may be referred to as ‘ajl, as Allah, subhanahu wa ta’ala (exhalted is He), says:

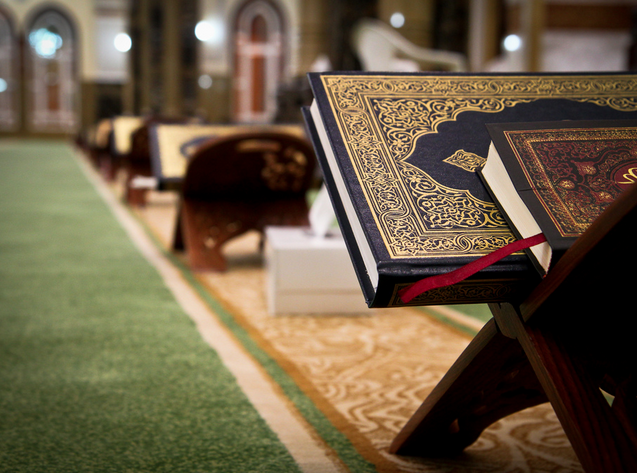

“And when those who disbelieve see you, [O Muhammad], they take you not except in ridicule, [saying], and “Is this the one who insults your gods?” And they are, at the mention of the Most Merciful, disbelievers. Man was created of haste (‘ajl). I will show you My signs, so do not impatiently urge Me” (Qur’an, 21:36-37).

In these verses, Allah (swt) mentions the traits of those who reject the message of Islam, and then informs us that humans are often by nature, inclined towards haste. They want to see the outcomes of their actions immediately; this is a description of the human psyche.

“And they (those who reject faith) say, “When is this promise, if you should be truthful?”” (Qur’an, 21:38).

This is an example of the worst form such haste may take, i.e. seeking the fulfillment of the promise of threat the Prophets would often make to those to whom they were sent to.

Finally Allah (swt) says:

“If those who disbelieved but knew the time when they will not avert the Fire from their faces or from their backs and they will not be aided…” (Qur’an, 21:39).

Thus the message is clear: there are consequences of what we do, whether good or bad, even though we may be heedless of it or want to see them immediately.

A closer look at these verses shows that Allah (swt) first mentioned the hasty nature of people, and then gives them an example of their hastiness. This is to emphasize and bring to attention this fact, something Allah (swt) wants us to actively strive against. ((See Mafātiḥ al-Ghaib by Imam Fakhr al-Razī))

Delayed gratification, however, requires us to have long term views, and unshakable conviction that what we are doing will eventually result in whatever it is that we are seeking and, most importantly, the patience (ṣabr) and perseverance (istiqāma) needed to get there, two qualities of which Allah (swt) says:

“And Allah is with the patient” (Qur’an, 2:249).

“So remain steadfast as you have been commanded, [you] and those who have turned back with you [to Allah], and do not transgress. Indeed, He is seeing of what you do” (Qur’an, 11:112).

As Imam Fakhr al-Rāzī mentions, steadfastness is one of the most difficult things for people, yet at the same time, it encompasses all aspects of the Islamic way of Life.

Short-Courses or ‘Intensive Courses’

All the above brings to the main purpose of the article: the increasing supply of short courses on Islam and intensive courses, which are often delivered in short exciting bursts and often with an overdose of hyperbole marketed in a similar fashion to other more conventional forms of entertainment.

Now from the outset, I’ll confess I have also organised short courses on Islam for a very well-known speaker here in the UK, and thus I’m not advocating that there’s anything inherently wrong with them, if they are delivered effectively. However, what I am worried about is the growing trend of such initiatives, which to an extent, seem to be replacing more traditional forms of learning, which requires at least a few years rather than a few weekends to complete.

I have even spoken to friends and some people who actively attend such courses who have admitted they have become ‘short course junkies.’ And therein lies the problem. I believe such courses should be the stepping stone on the journey of knowledge, or ideally for those who are unable to commit longer periods of time to the pursuit of knowledge, not the be all and end all. Yet such students should be aware that this does not give them claim to scholarship, which even though may seem far-fetched, some often do through their actions and the manner in which they engage in discussion of Islamic knowledge. Such courses do not allow for the development of scholarly acumen, which requires organic growth, requires one to make mistakes, and subsequently learn from them. A weekend or two hardly allows for that. They do not need much emotional commitment, patience and steadfastness. They are more akin to your ‘fast food’ outlets; They satiate your immediate needs, give you instant-gratification, but will not do for the more serious long term goals. Of course everyone is not required to be a scholar, but the limitations of short courses needs to be kept in sight, if we are to reap the appropriate benefits. They may give you an imān (faith) boost, and make you feel good about yourself, but that is only one part of knowledge. We should be careful of reducing our perception of knowledge to just gratifying and appeasing ourselves, which is fundamentally to do with our ego, whereas one of the fundamental goals of knowledge in Islam is precisely to curb the ego, ((See al-Muwāfaqāt by Imam al-Shātibī)) much of which is achieved through the process of gaining the knowledge itself. Knowledge is not to be reduced to mere entertainment.

The second best of this Ummah (Muslim community), ‘Umar radi Allahu ‘anhu (May Allah be pleased with him), spent twelve years on Sūrah Baqarah. It took his son, ‘Abdullah (ra), eight years to learn Sūrah Baqarah, and we all know who he was. The question that needs to be asked is, was this long duration due to a weakness in Ibn Umar, or does this say something more about how they used to learn and serve knowledge instead of it being vice-versa? Imam az-Zurqani (ra) answers in his commentary:

“It was not due his slackness, may God forbid… the disapproval for haste in memorizing the Qur’an was narrated from the Prophet.” ((Sharḥ az-Zurqānī ‘alā Muwaṭṭa Imam Mālik))

The kind of barakah present at their time is not present now. Al Maghrib uses short courses to reach a BA in Islamic Studies and that is their objective. Even though it may be a different way of learning I don’t see why that makes it worse. Subhanallah I do wish as a near-hafidh to spend so long memorizing Surah Baqara for 8 years, however, it just cannot be done with the lack of time between jobs, school, sleeping.

for at least six hours. Rather we could memorize it quickly then go back over it and refine it in my humble opinion. In today’s society you can do things slowly but not slow you stop doing the action

salam. I thought the mentioned eminent personalities spending all those years to “learn” surah baqarah referred to the process of implementing all of its lessons in their own life, not just memorizing the words. can someone verify/refute this?

mashallah

I think it is about being balanced and with the right intention. As learning is a personal responsibility in Islam, one should be conscious that just taking the short courses will not suffice it. You have to actually spend hours and sometimes months and years in a company of a teacher to really learn some stuff which simply cannot be taught in an “intensive course”. One should take the benefit of both.