When we listen to news stories that cause us distress, we are faced with the same question that those before us were faced with: what can we do? Definitely, getting involved and participating in relevant mediums of activism is part of the answer. Another part was once addressed by Jamāl al-Dīn al-Afghānī in his article titled, “The Way of Allah (in Dealing) with Past Nations and its Application for Muslims,” published in his news journal, al-‘Urwatu’l-Wuthqa, during his stay in Paris in 1884. Though al-‘Urwatu’l-Wuthqa only lasted about eight months with only eighteen issues, it became the medium through which his ideas spread internationally during that tumultuous time. Its influence and relevance persisted, even though the project was short-lived.

Included below is an excerpt from al-Afghānī’s article. Subhan’Allah (Exalted is Allah), the last part of this translation may be just as relevant today as the day al-Afghānī first wrote it. Preceding the translation is a relatively short biography of al-Afghānī. It has been included with the hope that it gives his words both context and added value. Readers are encouraged to comment with reflections on what is bold-faced in the translation. How can we apply al-Afghānī’s advice today?

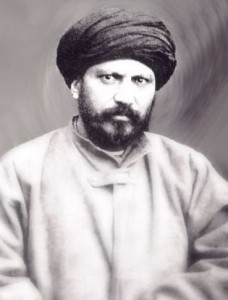

About Jamāl al-Dīn al-Afghānī

About Jamāl al-Dīn al-Afghānī

Born around 1838 or 1839, according to his own words, near Konar (close to the city of Kabul in Afghanistan), he was raised in a family who followed the Hanafi school of thought. His studies of philosophy and other sciences at the university level followed the medieval style that was prevalent in Kabul. He then studied in India and received a more modern education for a year, after which he made the pilgrimage to Makkah, and returned to Afghanistan in the service of the Amir Dust Muhammad Khan. As is evident from his writings, it seems his education allowed him a mastery over both Arabic and Farsi.

After the Amir’s death, his sons vied for power and al-Afghānī openly sided with the one who was later overpowered. He found it prudent to leave, and went back to India where he stayed for a few months, and then to Cairo where he stayed for forty days. In Cairo, he became acquainted with the students and scholars of al-Azhar, while he himself gave lectures in his home. By this time, he was around thirty years old.

In 1870, he went to Constantinople and was so welcomed there that he was allowed to lecture in the Aya Sofya and the mosque of Sultan Ahmed. It is interesting to note that he was able to communicate and be appreciated by the people in both Cairo and Turkey while he was from Afghanistan. Perhaps this communicative mobility also inspired some of his pan-Islamic thinking. He had to leave Turkey in March of 1871 because those who were jealous of his position started rumors about him; they changed the context of his words such that he would be called a rationalist or Mu’tazili.

He chose to go to Cairo, where he stayed longer than he expected to. He found a following of dedicated students including the likes of Muhammad Abduh and Sad Zaghlūl, and the government itself paid him a monthly salary without asking for any services in return. Seen as an educated dignitary, he was able to lecture on Muslim philosophy, politics, literature, science, and other topics. He inspired Adīb Ishāq to found various journals for which he contributed articles. According to al-Afghānī, journalism was the new popular medium that deserved investment, and a form of resistance via the written word.

He initially joined the Scottish Free Masons—only to leave and form an Egyptian lodge with the French Grand Orient. These moves by al-Afghānī show not a complete rejection of the West altogether, but rather just its imperialistic elements. It is said that the 300 young people who belonged to this lodge were Egypt’s most zealous nationalists. It was claimed that he verbally sanctioned the assassination of Khedive Ismail. These rumors put him at odds with al-Azhar and the Council of Ministers, and allowed the British to start heavily watching him until he was expelled in 1879.

He then went back to India, where he wrote his refutation against the materialists. The British who had colonized India during that time refused to let him go until the unrest (that presumably al-Afghānī had a hand in) was quelled. In 1881, Urabi Pasha revolted against the Khedive, the army, and the foreigners. In 1882, British interference ended the affair with their own occupation. After this, al-Afghānī could travel. In 1883, he was in Europe writing articles that were being published in major newspapers read in the Muslim world. In these articles, he commented on the conditions of various countries and criticized the interference of the British in particular. His refutation of Ernest Renan’s lecture on Islam and Science, which criticized the Muslim contribution in the modern era, was also published in Europe.

Working with Muhammad Abduh as his editor, they formed Al-‘Urwatu’l-Wuthqa, a journal for the Muslim world that would be used as al-Afghānī’s mouthpiece. Its entry into Egypt and India was barred by the British, and lasted only from March of 1884 to October of the same year. They sent it free of charge to anyone interested, and used strategies like placing the journal in mail envelopes to circumvent the British, and reach the people. Though short-lived, its impact was unmistakable as Islamic doctrines were used to encourage a response to the British interference in the Muslim world. However, in 1885, al-Afghānī and Abduh parted ways as a result of their strategic differences. Abduh emphasized education, while al-Afghānī supported political activism and resistance.

In 1886, the Shah Nair al-Din of Iran invited al-Afghānī to stay in Tehran, but that stay also proved short-lived. Al-Afghānī’s popularity was seen as a threat, and thus he was forced to leave. He then stayed in Russia until 1889, where he was able to convince the Tsar to allow publishing of the Qur’an and other religious texts for the Russian Muslim population. He was re-invited to Iran by the Shah, where he drew up specific plans of reform for the country. Yet once again, after a period of stay he was expelled to the Persian-Turkish border in 1891. This incident caused al-Afghānī to have an unrelenting distaste for the Shah—as would appear in his later writings. He criticized the Shah’s decision to allow the British Iran’s tobacco rights, which instigated the religious elite in Iran to immediately issue a fatwa banning tobacco for all Muslims. He also called on the Shi`i religious authorities to depose the Shah. It seems his words may have sparked the beginning sentiments that eventually led to the Iranian Revolution.

In 1892, Sultan Abdul Hamid invited al-Afghānī to Turkey. Initially, it seemed relations were good. However, after he rejected the position of Sheikh al-Islam for the government, the relationship soured. Al-Afghānī asked many times for permission to leave but his requests were turned down repeatedly. He did, however, have the right to teach and give lectures. He continued to preach his message of constitutional government within a pan-Islamic state until the Shah was assassinated by one of al-Afghānī’s loyal students in 1896. He wrote a refutation of his having any responsibility in guiding the hand of the assassin, as his own health was also precarious. Rumored to be poisoned, or given pseudo-treatment for cancer of the chin by his doctor under government instructions, al-Afghānī died in 1897. His many works became even more popular after his death, especially during the colonial struggles of the early and mid-twentieth century.

(Goldziher, I. “Jamāl al- Dīn al- Afghānī , al-Sayyid Muhammad b. Safdar.” Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Edited by: P. Bearman , Th. Bianquis , C.E. Bosworth , E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs. Brill, 2009. Brill Online. )

The Way of Allah (in dealing) with Past Nations and its Application for Muslims, by Jamāl al-Dīn al-Afghānī

“Verily, God does not change the condition of a people until they change what is within themselves” (Qur’an, 13: 11). These are the verses of the Wise Book, which guides to the truth and the straight path, and no one doubts in them except for the misguided. Does God go against His own promise while being the Most Truthful of those who promise and the Most Capable of those who can fulfill it?! Have Allah and His Prophet ﷺ lied? Has He forsaken His prophets and hated them? Has He cheated His creation and paved for them the path of misguidance? We seek refuge in Allah (from such thoughts)! Did he send down the clear verses in vain or in play? Did His Prophets fabricate against Him? Did they slander Him? Did Allah speak to His slaves by symbols they don’t understand and signs they can’t comprehend? Did He call them to Him by what they cannot conceptualize? We ask forgiveness from Allah (for such questions).

Has He not sent the Qur’an in Arabic, without mistake, and explained in it all matters, clarifying all things? His Attributes are sacred and Allah is Elevated, a Great Elevation, above what the transgressors say. He is the Most Truthful in His promises and threats, and has never taken His Prophets as liars. He never brought anything for play, and He did not guide us except to the path of guidance. There is no replacement for His verses. The heavens and the earth can perish, but a law from the laws of His book would never perish, as falsehood can never approach it, from before it or behind it.

God states, “Certainly, We have written in the book [of Psalms] after the [previous] reminder that My righteous servants shall inherit the land” (Qur’an, 21:105). He also states, “…to Allāh belongs [all] honor, and to His Messenger, and to the believers” (63:8), “And incumbent upon Us (God) was support of the believers” (30:47), and “It is He who sent His messenger with guidance and the religion of truth, that He may make it prevail over all other religions; and sufficient is Allāh as a Witness” (48:28).

Allah caused this nation to emerge from a handful of believers, and took it to such heights of greatness that many hearts trembled in fear of it. Indeed, a people who were true to their covenant with Allah earned deeds that allowed them glory in their worldly lives and happiness in the afterlife. This Ummah today has reached about 280 million people and its lands, as previously discussed, stretch from the edges of the Atlantic Ocean to the ends of China. Blessed with good soil, fertile plantations, spacious homes…yet, its lands are being plundered, and its wealth robbed. Intruders are taking over the people of this Ummah. They are dividing its lands among themselves, country after country, province after province. It is left neither with authority, nor with a voice. Its torchbearers find themselves in pain by day and in distress by night. Their time has become constricted by the increasing catastrophes that have gathered upon them, and their fears have become greater than their hopes.

This is the same nation that collected the jizyah (compulsory tax for non-Muslim citizens of an Islamic state) from large nations to look out for them. Oh what a disaster! Oh what a loss! Is this not a calamity?! What is the reason for this decline? What has caused this fall and humiliation? Should we be suspicious of divine promises? Should we despair from Allah’s mercy and think that He has lied to us? We seek refuge in Allah (from such thoughts). Should we doubt His promise of victory to us after He has affirmed it for us? No, it is none of that. It is upon us then to look at ourselves, and see that there is no one for us to blame except ourselves. For He said, “And you will not find in the way of Allah any change” (63:62).

He, The Most High, showed us through His clear verses that nations He has honored do not perish or fall from greatness. Their names are also not erased from the tablet of existence, except by their deviation from the ways Allah established on the foundation of extensive wisdom. Allah does not change a condition of a people to honor, authority, luxury, living, safety and comfort, until those people change what is in themselves—through illumination of the mind, soundness of thought, and depth of vision; from taking lessons from the actions of Allah with previous nations, and reflecting on the situation of those who joined forces against the path of Allah—for they were destroyed—and those who neglected the practice of justice, and left the path of insight, resolution and wisdom—for they were ruined.

Unite together in commitment to righteous work, truthfulness of speech, soundness of the heart, chastity in the face of desires, and protection of truth, standing for its victory, and cooperating in its protection!

(Ammara, Mohammad. Jamal al-Din al-Afghani, al-A`mal al-Kamilah. al-Mawsu’ah al-Arabiyah li’l-Dirasat wa’l-Nashr: Beirut 1988. V.2 pp. 58-60).

[…] June 28, 2010 readers were encouraged to comment on how to apply the advice of the following translated piece […]

Your article was excellent and edritue.

His writings inspired people in my country, to no longer be docile under the colonial yoke, which then led to our successful bid for independence. And I daresay it helped produce the generation of selfless, principled people that looked after the country in its infancy, so that we had a head start of some decades of genuinely honest development while others achieving independence at the same time as us in Asia and Africa descended into civil war, despotism, and corruption.

That generation is gone, and our nation yet reaps the benefits in the wake of their service, but I cannot say those who followed after them are nearly so principled. So I hope my people can become again so thoughtful, learned and courageous, before our nation goes the way so many others have gone.

This article deserves more than two comments. I think that his last paragraph was the most meaningful while everything preceding was basically conventional understanding, at least for me. The last paragraph was pretty interesting and I wish he had expanded on it. It does appear to be that the sunnah of Allah is to degrade a country from comfort when it has fallen morally.