By Lubaaba Amatullah

When asking fellow Muslims about the first English Qur’an, the response is frequently a reference to the 1930 translation by Muhammad Marmaduke Pickthall. Less frequently an excited voice speaks of the George Sale Qur’an of 1734. However, British Islamic – and Qur’anic – history extends long beyond that, in a rich account of theological study, political negotiations and self-discovery.

The entrance of the complete Qur’an into the Western world is in fact traced back to the Middle Ages. The first translation into a European Western language, Latin, was completed by the English scholar Robertus Retenensis. It was entitled ‘Lex Mahumet Pseudoprophete’ (‘The Law of Mahomet the False Prophet’) and was completed in 1143. The translation enjoyed popularity and wide circulation, and was later to become the main basis for further contemporary translations into Italian, German and Dutch. ((Abdul-Raof, Qur’an Translation: Discourse, Texture and Exegesis [Routeledge, London, 2001], p. 19)) Between 1480 and 1481, not long after the fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans in 1453, the first bilingual translation into Latin with accompanying Arabic appeared, composed by the Jewish convert to Christianity, Flavius Mithridates. ((Ziad Elmarsafy, The Enlightenment Qur’an [Oneworld, Oxford, 2009], p. 3)) In 1647, Andrew Du Ryer produced the first French translation in Paris. The first direct translation from the Arabic text since the Middle Ages ((Elmarsafy, The Enlightenment Qur’an, p. xi)) , it was a marked improvement from those produced in the years since 1143.

Title page for the first English translation of the Qur’an (1649) by Alexander Ross

Title page for the first English translation of the Qur’an (1649) by Alexander Ross

It was from Du Ryer’s translation that the first English translation was produced in 1649: ‘The Alcoran of Mahomet’ (( Alexander Ross, The Alcoran of Mahomet, Newly translated out of Arabique into French by the Sier Du Ryer, Lord of Malezair, and Resident for the King of France, at Alexandria. And Newly Englished for the satisfaction of all who wish to look into the Turkish Vanities [London, 1649] )) by Alexander Ross. It was rendered from the French rather than the Arabic, making it an indirect translation with all the associated problems of inaccuracy. Nonetheless, the Ross translation is important both as the first complete print of an English Qur’an and also for the significance of the time in which it was produced.

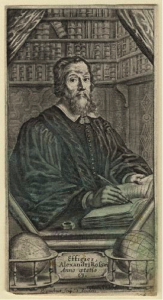

Alexander Ross (1591-1654), Clergyman and writer.

Alexander Ross (1591-1654), Clergyman and writer.

Engraving in 1653 by Pierre Lombart, (1612 or 1613-1682)

The early modern period endured a time of upheaval in Christian Europe in both religious and national identity. In addition to the tensions created by increasing sectarian conflicts among Christian sects, the expanding Ottoman Empire placed considerable pressure on Christendom. Islam was expanding both demographically and geographically ((Nabil Matar, Islam in Britain: 1558-1685 [CUP, Cambridge, 1998], p. 17)) , through the superior military might of the Muslim Ottomans and the conversions of European Christians to Islam. ((Matar, Islam in Britain, p. 19)) The faith simultaneously threatened and attracted Christian Europe as both conflict and conversion flourished. Richard Knolles, an early English historian who in 1603 wrote The Generall Historie of the Turkes, the first major text on the Ottoman Empire in the English language, commented in it on the impossibility to ‘set downe the bounds and limits’ upon the Ottomans who accept ‘no other limits than the uttermost bounds of the earth’. The Ottoman threat made the translation and dissemination of the Qur’an a matter of urgency to inform the public of the ‘true’ Qur’an (according to how the polemical translations would portray it), prevent further conversions, and educate people on how to draw Muslims to Christianity ((Elmarsafy, The Enlightenment Qur’an, p. 4)) . The threat was particularly real for Britons who suffered from conversions, piracy, and the general military might and economic superiority of the Islamic Empire.

Besides the external troubles from the Ottoman faith, Britain was also undergoing significant upheavals from within. The English Civil War between the Parliamentarians and Royalists was underway, with 1649 seeing the conclusion of the second war, the execution of King Charles I and the establishment of the short-lived English Republic. That this year produced the first English translation of the Qur’an, merely four months after the fall of the monarch, and by Ross, who was a known Royalist ((Nabil Matar, “Alexander Ross and the First English Translation of the Qur’an,” The Muslim World, Vol. 88 [1998], p. 84)) and beneficiary of Charles I ((Matar, Alexander Ross and the First English Translation of the Qur’an, p. 82)) , is no coincidence.

The publication of the Qur’an at this central moment in the re-defining of Britain’s identity and national dynamics is an historical event whose significance has been neglected. To argue that the Ross Qur’an was minor and coincidental would be a mistake. The translation enjoyed popularity during the seventeenth century, subsequently overriding the George Sale Qur’an of 1734 to become the first translation printed in the United States in 1806 ((Elmarsafy, The Enlightenment Qur’an,, p. 9)) .

Published four months after the regicide of Charles I and the establishment of the English Republic, under which there were serious upheavals in the Church of England, the translation was arguably a response to a government considered by Ross, a previous chaplain to the deceased King, as heretical and sinful for executing their divinely anointed monarch and restructuring the holy Church. Here, the translation of the Muslim holy book entailed an attack upon a despised government through comparison to a rejected faith: Islam. In the introduction and appendices, the authorities are accused of ‘instability in religion’ ((Ross, The Alcoran of Mahomet: A Needful Caveat)) and compared unfavourably to the heretical Muslim Turks. However, even as the authorities are faulted for being ‘too like Turks,’, soon after Ross admiringly describes the Muslims:

”… how zealous they are in the works of devotion, piety, and charity, how devout, cleanly, and reverend in their Mosques, how obedient to their Priests, that even the great Turk himself will attempt nothing without consulting his mufti…” ((Ross, The Alcoran of Mahomet: A Needful Caveat))

While the Turk may be heretical, the authorities were both heretical and immoral; in character the Muslims were deemed better. In one breath condemned for being Turk, in another condemned for not, the instability of British identity and the struggles to frame it in this difficult moment is evident. Through the internal conflict of civil war, wherein a sense of the English self was destabilised, the English Qur’an became a medium through which to turn to the stable Turk as a balancing figure in the process of self-negotiation; one to compare against and, in spite of the Christian reflex against an infidel, to emulate.

Significantly, this attitude to the Ottomans is also portrayed by the Parliamentarians. The 1649 Secretary for Foreign Tongues and famed poet, John Milton, praised the Muslims for their ability to ‘enlarge their empire as much by the study of liberal arts as by force of arms.’ ((John Milton, ‘Prolusion 7’ in Complete Prose Works of John Milton, 7 vols., gen. Ed. Don M. Wolfe [New Haven London: Yale University Press, 1953-1983], vol. 1, p. 299)) Like Ross, the authorities were torn between rejection and admiration of the Muslims, employing this heathen other as a balancing figure in understanding English identity and projecting aspirational paths of political advancement.

Ultimately, Ross’ translation became not only the first English Qur’an, but a text of the English Civil War and a crucial tool in its political struggle and negotiation of a national identity. Through the turbulence of conflict, the Islamic holy text found itself transported and adopted into a new realm, one that was experiencing the pangs of its rebirth, and impacting at the very roots of the conflict. The Qur’an became a symbol of the ideological struggles of the revolution, leaving its indelible mark on British identity and history.

Lubaaba Amatullah is joint Editor-in-Chief of The Platform (www.the-platform.org.uk). When not consuming tea or waxing lyrical on the glories of British chocolate, she pursues a PhD in English Literature exploring England’s early encounters with the Islamic world.

As salamu ‘alaykum, Lubaaba apu. Nice to see your writing on suhaibwebb. Very informational and intriguing piece of writing.

[…] Abdul-Raof, Qur’an Translation: Discourse, Texture and Exegesis [Routeledge, London, 2001], p. 19 [↩] […]

It very Good for increasing of inspiration about “quran” telawat.

Excellent piece of writing discovering many unknown information for the inquisitive readers.

Thanks for putting a such wonderful research of information. Did not know much beyond some early french/latin translation.